Historic New England envisions the Haverhill Center for Preservation and Collections as a catalyst for a global-national-regional-local arts and culture district in downtown Haverhill, Massachusetts.

A BOLD NEW VISION

Explore living archives, state-of-the-art storytelling, and pioneering exhibitions. Experience dynamic installations and performances by world-class artists breaking new creative ground. Expand your knowledge with hands-on learning opportunities from top innovators and makers. Get excited.

Historic New England will evolve its downtown Haverhill location to unprecedented visitor and exhibition spaces and partner to develop residential, innovation, hospitality, and dining facilities. The Haverhill Center will support an improved streetscape, including expanded public art, lighting, signage, and green space.

This cultural district will serve as community catalyst, strengthening local and regional businesses, arts, environmental, and social institutions and significantly drawing new visitors and revenue to the area.

“We envision collaborating with the community to develop sustainable, more livable, resilient, and dramatically improved amenities, anticipating that the impact of the downtown cultural district will reverberate internationally.”

—Vin Cipolla, president and CEO, Historic New England

Boston’s Designer Shoe Renaissance Has Lady Gaga’s Feet

WHAV: State Budget Targets Funds for Historic New England Haverhill Center

The Haverhill Center on Chronicle

Conversation: Factory Reborn: Reviving Industrial Roots in Haverhill and America

WHAV: Historic New England Awarded Office of Travel and Tourism Grant

WHAV: Historic New England Recognizes Romano with 2024 Prize

CEO and President Vin Cipolla on The Culture Show with Jared Bowen (at 30.30 point)

CEO and President Vin Cipolla Named One of Top 25 North Shore Influencers of 2024

Click here for more news!

upcoming events

You can help shape the vision for the Haverhill Center. Join us at community events around the city that showcase exciting stories, creative activities, and compelling traditions. Please come see us to learn more about our vision for the Haverhill Center and become part of the story.

FIND YOUR STORY

EXPLORE THE COLLECTIONS

Historic New England’s collection includes more than 125,000 objects and over 1.5 million archival documents. From teddy bears to tattoo flash, there’s something for everyone! To understand the breadth of the collection and the many stories it contains, you can explore a small sample below.

1735-1745 A gold and dark brown landscape of birds, Chinese architecture, bridges, human figures, large fantastical animals, and an abundance of flowering plants plays across the drawer surfaces on the façade of this Boston high chest. The decoration is known as “japanning” and was done in imitation of Asian lacquer furniture. The craftsperson, or japanner first decorated the surface with vermillion streaked with lampblack to imitate the appearance of tortoiseshell. The craftsperson then created raised figures with gesso and coated them with gold and black paint. The japan work is thought to be that of Robert Davis, an English-born japanner who worked in Boston until his death in 1739. Josiah Quincy (1710-1784), a wealthy merchant originally owned the piece. It was rescued from house fires, not once, but twice, before 1770. In 1769, after the second fire, Quincy wrote in his account book "the greatest part of my furniture [was] by the timely assistance of our friends and neighbors, secured from the devouring flames." Decades later, Josiah's great-granddaughter, family historian Eliza Susan Quincy, wrote the story of this high chest's survival on a small paper label which she pasted inside a drawer. Today the chest is valued not only for its rare japanning decoration, but for its well-documented history. It is on display at the Quincy House in Quincy, Massachusetts.Fantastical Landscape

Eastern white pine, red oak, red maple

Historic New England Haverhill Center is located in one of the largest former shoe factories in Haverhill. In 1900, 40% of the country’s shoes were manufactured in Massachusetts and Haverhill—“the Queen Slipper City”—was the third largest shoe manufacturing city in the United States. Adapting to changes in fashion and with the advance of organized labor, the Haverhill shoe industry continued to flourish. In 1941, a profile of Haverhill boasted the city as the largest manufacturer of women’s shoes in the US, with over fifty shoe factories in the city, along with other associated businesses in wooden-heel manufacturing and leather tanning. Queen Slipper City

Artist Sierra Autumn Henries creates contemporary jewelry inspired by her Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuc heritage for powerful patterns and traditional materials. “Many native cultures across the world, including my own, had and have been using birch bark for countless generations, and I feel honored to carry on that tradition.” –Sierra Autumn Henries

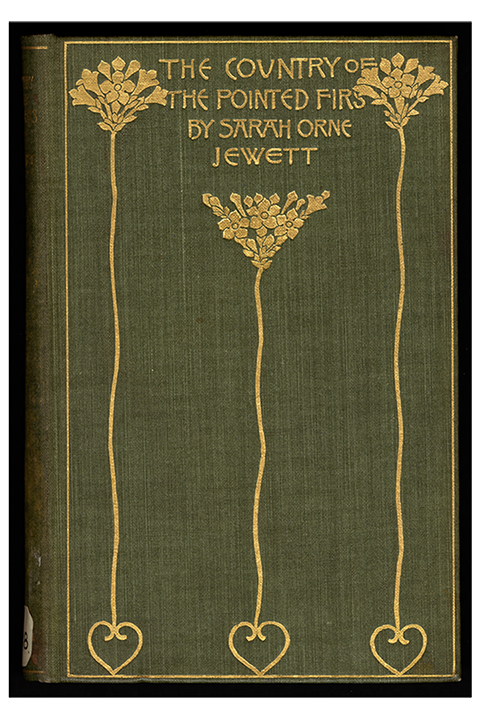

Iconic Maine author Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) is best known for two of hermajor works, The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896) and “A White Heron,” (1886). In her day, Jewett was an internationally celebrated author. She wrote over threehundred works, including fiction, essays, and poetry.By the late twentieth century, Jewett’s fame had declined. Much of the reason for herdiminished light is the literary criticism, white-male-centered, that dominated themid-twentieth century. Dismissed as quaint and regional, Jewett’s contribution toliterature was overlooked. Recently, scholars have rediscovered her work and there isrenewed interest in the deft depictions of women, the subtleties of relationships, andthe feminist undertones in her work, notably her 1884 novel, A Country Doctor.Central themes of Jewett’s work reflect her own life: often, protagonists seek to freeof literal or figurative barriers, as Jewett carved out a life of literal and artistic freedomin her life, exchanging a traditional wife role for that of writer; themes of nature playstrongly in transcendentalist motifs referencing Jewett’s strong connection to thenatural world; themes of community reference the importance of Jewett’sfriendships, particularly female friendships in her life and as the inner circle of theprivate world she shared with partner and the love of her life, Annie Fields.Sense of place—Maine in particular--is prominent in the work of Sarah Orne Jewett,whose home in South Berwick, Maine, now a Historic New England site, was a belovedconstant in her life and she once wrote that she was “made of Berwick dust.”Breaking Free

In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century New England, while men were building communities through fraternal organizations or at the tavern, women's communities centered on the church, on charitable works, and on sewing and reading circles. Joining neighbors for a day of quilting was a highlight of the season for many New England women. So-called "friendship" quilts came into vogue in the 1840s. This was a time of extensive migration in America, with families moving west, or leaving their farms for opportunities in mill towns and cities. These quilts were often given as remembrances to departing neighbors. Friendship quilts contain squares with stitched or inked signatures. The point was to offer a token of affection to the recipient. This red and white quilt was made between 1851 and 1853 by members of the Howard Sunday School of the Bulfinch Street Church of Boston, apparently for Sunday School teacher Francis Cogswell Manning. The quilt may have been a gift marking Manning's anniversary as a teacher at the Sunday School. A note by Francis Manning that survives reads: "You have taken me entirely by surprise, fellow teachers [and friends], by this unexpected mark of your favor, and I feel entirely unable to give expression, in any fitting words, to the feelings your kindness has awakened in my heart."

Circle of Friends

Photograph of the China Trade Gate, colloquially known as the Chinatown Gate, in Boston, Massachusetts. This photograph was taken in 2017 by John D. Woolf as part of a series intended to highlight threats to Chinatown from gentrification and development. Signed by John D. Woolf on verso. John Woolf (b. 1952) has worked as a photographic artist for more than forty years. His photographs of Boston’s Chinatown and diners in the Northeast are part of his effort to document the transformation of the American urban architectural landscape and the fast disappearing twentieth-century roadside architecture of the Northeast industrial corridor. Woolf’s photographs document the Chinatown many are hoping to preserve. The gateway, proposed by noted Boston entrepreneur and longtime community activist “Uncle” Frank Chin, was commissioned by the China Trade Center, designed by architect David Judelson, and gifted from the Taiwanese government to the Chinese community of Boston in 1982. Made of painted steel tubing on a concrete base, the paifang, also known as pailou, archway at the Beach Street entrance to Chinatown was installed in 1988 and rededicated in 1990.Urban Landscape

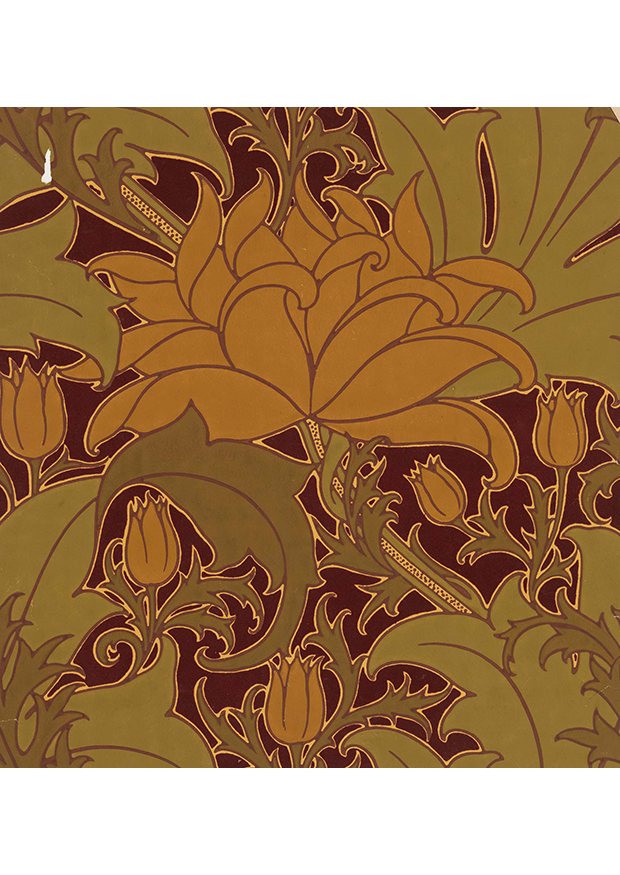

C.F.A. Voysey Wallpaper A founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement, architect and designer Charles Francis Annesley Voysey created wallpaper patterns of whimsical simplicity incorporating stylized depictions of the natural world. This unused ca. 1893 sample in the Historic New England collection is a good example of Voysey’s stylization, with a large-scale flower surrounded by leaves and flower buds. Printed in olive, two greens and gold on a crimson flocked background. A response in part to the Industrial Age, the Arts and Crafts movement began in late nineteenth century Great Britain and spread to America. The Arts and Crafts movement had varied modes of expression unified by the characteristics of devotion to craftsmanship, marriage of beauty and utility, and inspiration from the natural world.

Devotion to Craft

1893

This teddy bear belonged to Susan Norton (1902-1989), who at the age of four, brought it along on a trip to Rome. This particular bear is a very early specimen (teddy bears were first manufactured in 1902). It is remarkable that is survives in such good conditions, especially considering its world travels. The iconic Teddy Bear was so named after President Roosevelt, who refused to shoot a bear cub during a hunting party in 1902. The event was memorialized in a Washington Star cartoon that inspired Brooklyn store owner Morris Michtom to make a stuffed toy bear cub for a store window display. The bear’s popularity prompted Michtom to found the Ideal Toy Company, later one of the nation’s leading toy producers.

World Traveler

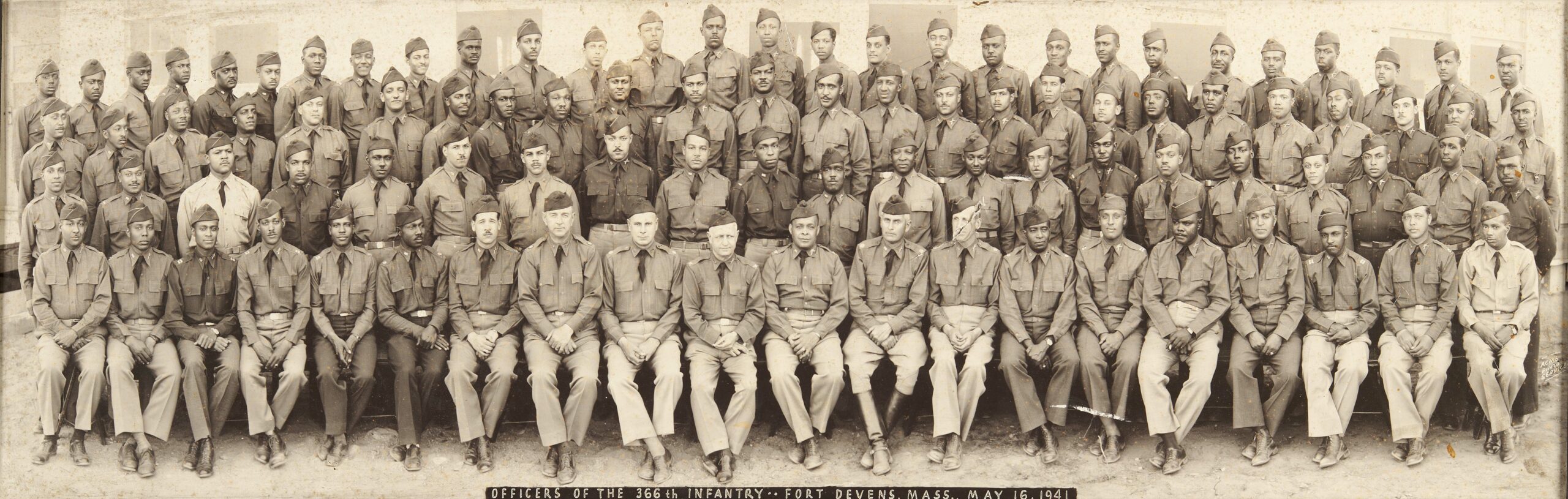

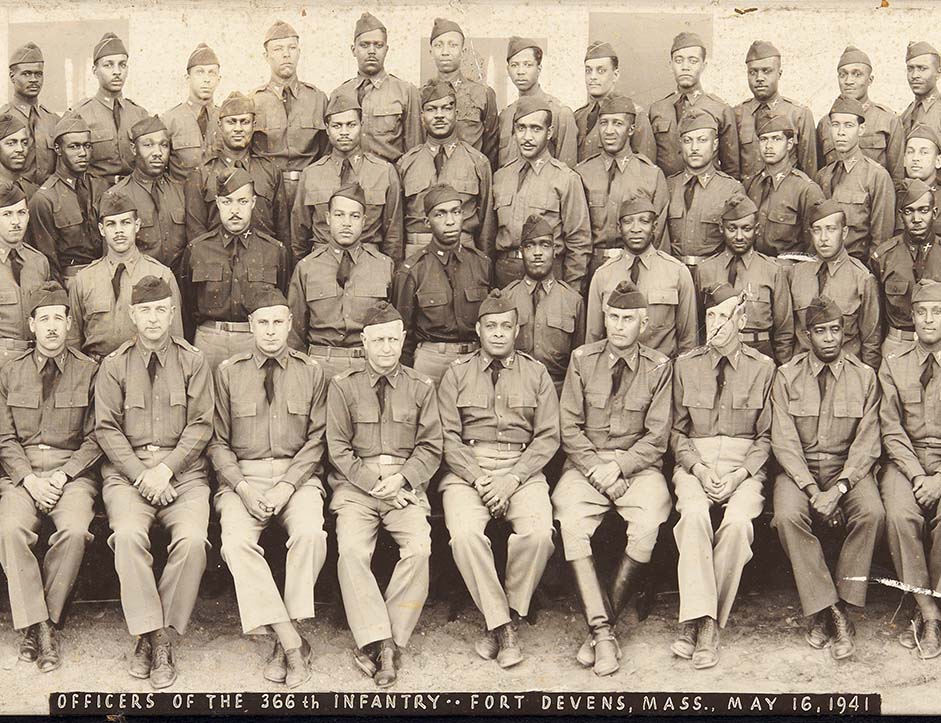

The 366th Infantry Regiment was a segregated, all African American unit of the United States Army. The unit served in both World War I and World War II. In World War II, all of the officers and troops within the unit were black. However, their field grade officers (major or above) and company grade officers (second lieutenants, first lieutenants, and captains) were white. The United States military did not desegregate until 1948, when then President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981. This order abolished discrimination in the United States Armed Forces.

American Soldiers

De Morgan, William Frend (1839-1917) This ceramic tile with a design of sunflowers and leaves in rose lustre and white, and enclosed in a wooden frame, is attributed to William De Morgan (1839 – 1917), a leading innovative designer of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Images of sunflowers proliferated the decorative arts in England and America in the 1880s. Their association with lasting happiness and adoration made them a favorite for both the Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts Movements. Sunflower motifs were featured on wallpaper designed by William Morris, on fireplace tiles by William De Morgan, and in newspaper illustrations showing the bon vivant Oscar Wilde, a central character in the aesthetic movement. Trained as a fine artist, William De Morgan became interested in the decorative arts as a young man, embarking on a lifelong friendship with William Morris. Turning his attention from painting to stained glass, pottery, and tile design, De Morgan was led by his scientific curiosity to rediscover and innovate the lustrework technique found in Hispano-Moresque pottery, which incorporated Islamic and European elements, and maiolica, Italian Renaissance pottery. His work was influenced in color and design by Iznik ware motifs and featured stylized depictions of nature interwoven with geometric patterns. Best known for his work in ceramics, De Morgan also designed furniture and later wrote a series of popular novels.Happy Motif

Decorative Tile in Frame

Ceramic tile, wood

Bequest of Susan B. Norton

Walter Gropius, founder of the German design school known as the Bauhaus, was one of the most influential architects of the twentieth century. Escaping Nazi Germany, he designed Gropius House as his family home when he came to teach architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Historic New England preserves his home in Lincoln, Massachusetts, and many of the household objects he designed.Icon of Modernism

Historic New England Haverhill Center

Historic New England is the largest cultural real estate presence in Haverhill, Massachusetts. Our campus is conveniently located approximately 35 miles north of Boston in Haverhill’s historic downtown and easily accessible by Amtrak, MBTA Commuter Rail, and three major highways.

SUPPORT THE VISION

To learn more about the Haverhill vision and how your philanthropy can have a transformational impact, please contact Elliot Isen, Haverhill campaign officer, at [email protected]

CONNECT WITH US

Let us know your thoughts

We’d like to hear from you!

"*" indicates required fields

STAY UP TO DATE

Sign up for updates on the Haverhill Center project

ABOUT HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND

Historic New England—founded as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities on April 2, 1910—serves as a leader in historic preservation in the New England region and beyond and is one of the most comprehensive independent preservation organizations in the United States. Historic New England welcomes the public to thirty-eight exceptional museums and landscapes, including several coastal farms.

The organization operates a major collections and archives center in Haverhill, MA, and has the world’s largest collection of New England artifacts, comprising more than 125,000 decorative arts and objects and 1.5 million archival documents including photographs, architectural drawings, manuscripts, and ephemera. Engaging education programs for youth, adults, and preservation professionals and award-winning exhibitions and publications are offered in person and virtually. The Historic New England Preservation Easement program is a national leader and protects 127 privately owned historic properties throughout the region.